I am outsider, not a ne’er-do-well or a misfit, just someone who has found contentment on the outer edge. I can trace the heritage of this feeling to a convergence of experiences. I moved 3,000 miles — from an enormous city to a small hamlet filled with people revered for never leaving — all while ‘coming of age.’ It felt entirely disastrous.

____________________________

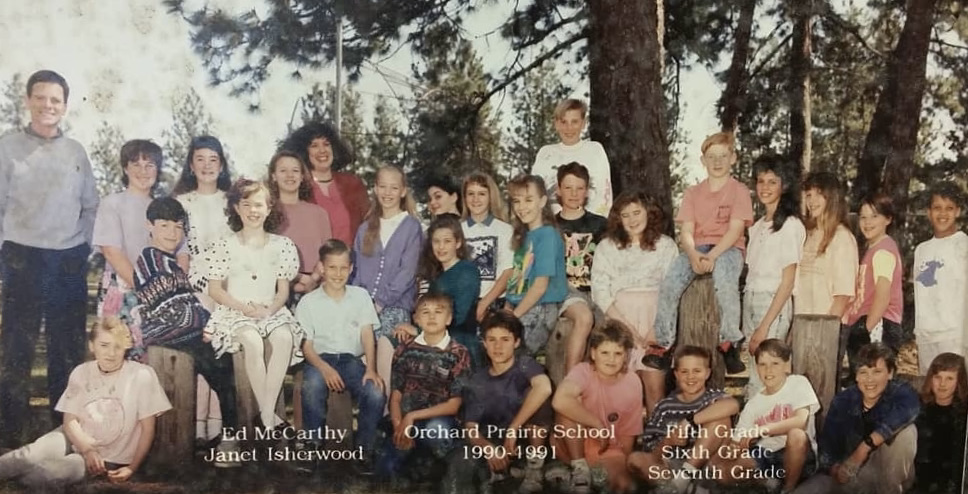

My parents laced their way from Orlando to Spokane through swamps, deserts, plains, and mountain passes in November of 1990. I was a shiny penny my first week of fifth grade at Orchard Prairie, a tiny speck of a school with 50 students kindergarten through seventh grade. I was a little exotic having come from a distant and inconceivable land. There were more people in spitting distance in the sprawling suburbs of Orlando than the entire backwards tight-knit community where I found myself transplanted. Two boys chased me around at recess as a testament to their short-lived affection. Regardless of the fact that we returned to our fourth-generation family home, I maintained ‘other’ status without exception or review.

In the beginning I studied the peculiarities of this closed ecosystem in an attempt to morph into a “prairie kid.” This did not come together as I had hoped. I remember the bizarre speech of my new peer group. Everyone called a classmate’s brother Germy, instead of Jer-e-my. They glued two whole syllables of his name together. They pronounced crayons crowns. I tried out the colloquial way of speaking and it felt all wrong in my mouth. I couldn’t remember to speak like everyone else and I finally gave up. Maybe that is how everyone knew I was an outsider.

Or maybe it was the way I dressed. I hailed from the pseudo-south where dressing to the nines was considered socially acceptable and, more often than not, absolutely prudent. For my first school picture day, my mother put my hair in sponge rollers the night before and I wore my prettiest dress. The photographer used a play structure on the playground to arrange us — large posts the thickness of telephone poles in various heights. Some of us sat on top of the posts, some stood interspersed, while the rest took a knee down front. I perched on a pole with my hair as curly as Shirley Temple in my best drop-waist dress with puffed sleeves. My feet were crossed at the ankle and my hands were folded in my lap. I looked like a frosted cupcake in the middle of kids wearing neon t-shirts, acid washed jeans, and scuffed tennis shoes.

I didn’t speak or dress the same and I couldn’t catch a kickball worth a damn. I was the last to be picked for any game involving teams and a ball. I was remarkably small and wiry, though not bookish or a loner. I was no stranger to playing. I knew how to ride a bike, play in the dirt, and construct a make-shift shelter out of scrap lumber, none of which were recess-ready skills. My parents were not ball-admiring people — no mitts and baseballs, no soccer ball or basketball on the premises. To this day the mechanics of throwing a football eludes me. I was conscripted to the sidelines. I was aghast when all my usual charm and charisma resulted in scorn and disdain.

There was a clear definition of what it meant to be on the inside and I couldn’t pass muster. I was desperate to be included and embittered that being a “prairie kid” was out of reach. It would take many years before the sting of rejection subsided and I could look on my own unique self with appreciation.